| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Theory of Production & Costs | The growth of firms |

The growth of firms

Firms usually start small, often as a one-person concern or a family concern. According to Barclays Bank, some 465,000 new firms started up in 2003 alone. Sadly, many of these are doomed to fail. According to government statistics, in 1997, the business survival rate for new firms was only 65.1 per cent after three years; one third had disappeared in that period. About half of these close down voluntarily, and about a third sell the business to another firm.

In many cases they are undercapitalised, and the firm simply runs out of money and cannot borrow any more. In some cases it is a management constraint, in that the person is ambitious but not talented or skilful enough. Virtually all firms have to borrow to invest and grow.

Why do firms wish to grow?

The usual motives are:

To make higher profits.

To establish a business that will see them through life.

To leave a legacy for their dependents and perhaps to establish a dynasty.

Reasons for success are harder to pin down, but include:

Sufficient capital to tide the firm over a bad patch. Access to funds.

Good contacts.

Willingness to work long hours.

Developing a strategy to overcome local or regional disadvantages in location. Developing a niche market or a unique selling point.

The desire for to grow leads firm to try to increase their share of the market. The really successful ones may gain economies of scale and a few might become monopolies or be large enough to compete with the big boys.

4-2. THE MOTIVES OF FIRMS

1. Profit maximisation.

In economic theory, the main motive for a firm is to maximise profits. This is central to mainstream theory. It involves equating marginal cost with marginal revenue, whatever the market situation the firm is experiencing.

2. Revenue maximisation

This is another suggested goal. It would be possible for a firm to survive following this goal but it would grow more slowly and always be a bit at risk. A lusty profit maximiser could seize an increasing share of the market, possibly driving the revenue maximiser out in the longer term.

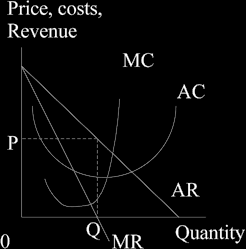

Using our diagrams, instead of the firm seeking the point where MC=MR as a profit maximiser would, the revenue maximiser keeps expanding output as long as marginal revenue is positive. It ceases to be positive where it cuts the horizontal axis at Q in the diagram below. As soon as it becomes negative, total revenue would start to fall, so the firm stops.

In the above diagram, the revenue maximising quantity is thus OQ and the price is then read off the demand curve: the firm chooses price OP.

Because the firm reduces price until marginal revenue becomes negative, there is an implication for the elasticity of demand. If a price reduction leads to an increase in total revenue, we know that demand is elastic. If a price reduction leads to a fall in total revenue we know that demand is inelastic. As we switch from increasing to falling total revenue, the elasticity of demand must be neither – it is unit elastic at that point.

3. Sales maximisation

This is a third suggested goal. It suffers from the same problem of the revenue maximisers, in that the firm is vulnerable to profit seeking competitors.

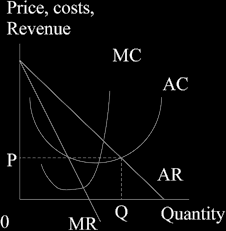

Such a firm will expand output until the average cost curve intersects the demand curve, as in the diagram below.

The firm produces OQ level of output and sells it for price P. This price is lower than the profit maximiser’s price, or the revenue maximiser’s price – as one would expect as more sales is what it is all about.

A variant of this model is that the firm may concentrate on maximising sales in the short term in order to gain a larger share of the market so that in the long term it can earn more profits by switching its goal. It is a sort of long term profit maximiser using the route of short term sales maximisation!

Another business variant model of the sales maximiser is that it is possible that when the firm becomes large, managers are taken on and they may prefer to maximise sales rather than profits. The shareholders would generally prefer higher profit but they have little say in day to day running of a company.