| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Why Markets Can Fail | Reason 8 - Factor immobility |

Reason 8 - Factor immobility

The factors of production that we have are land, labour and capital plus a remainder term (L, N, K, + R) – most economists and textbooks focus on labour immobility, but this is not guaranteed for the exam!

We can also have land immobility

• Some land is good for growing one or two particular crops and not very good at some other crops. It is not easy to change rice (which needs wet soils) to wheat (which needs drier conditions).

• It is not possible to move land from where it is to somewhere else.

• Climate change may be occurring and farmers are often traditional, growing what they or their family have done for years or even generations. They may be unaware of, or refuse to try growing, a now more suitable crop.

• Economic Union subsidies keep many farmers’ attention on producing the crops that are highly subsidised (as it gains them a higher income) rather than what might be more suitable for their land or sell better. Quite often the EU gets it wrong, so

we ending up with a lot of produce that is hard to sell. Dumping it on international markets annoys other countries that produce such goods efficiently as it reduces their market. Dumping it into the sea causes criticisms of waste in a world of poverty.

And capital immobility

• Some capital is specific e.g., it makes light bulbs, and it cannot be transferred to another use, like producing ball point pens.

• Some capital is very big and heavy, e.g., a steel mill, and it is difficult or impossible to move it to another geographic areas.

• Some old decaying industries may be subsidised by government and continue to exist for years, well beyond their shelf life. This keeps the capital (and the associated land and labour) where it is so that it is not released for use where it is more wanted by society. That is to say, government subsidises prevent factors of production moving to turn out what people now demand. The fact that the industry is decaying shows that demand has changed and people no longer want that good or service as much as they once did.

• Some (usually small) firms stay in business despite making poor profits because the owner does not want to move or to cease production; or perhaps the owner is too

old to bother to make any major change.

Labour immobility (the really interesting one – we ourselves are people!)

Geographic immobility of labour

• People do not up and move easily from Leeds to Watford, just because they can earn £20 a week more there. Even less do they move from Tours in France to Hull in Yorkshire.

• People are usually happy where they are: they have got relatives and friends, they know the town and area, and they are members of various clubs and other social groupings. They do not wish to move.

• They may not know about the extra £20 they could get if they were to move (“information failure”). Information failure actually costs money to overcome: people must pay to use the Internet, or have to buy newspapers and magazines.

• Moving house costs money: there are estate agents’ fees, lawyers’ fees, a government stamp duty and the cost of transporting furniture and all the other household effects.

• Inertia: people often do not like a big move as they have a sort of fear about it, so they just stay where they are.

Institutional immobility of labour

• Trade unions and government pass rules or laws that prevent people from entering a new job easily.

• Pension schemes may tie people into a particular company – if a worker moves, he or she will probably lose the amount paid in by the employer on their behalf (this can amount to several thousand pounds).

• Council houses (state subsidised housing) are let below market rents and can prevent people moving; if they move it means they must give up their cheap house unless they are able to arrange for a house-exchange with another council tenant.

• Foreign-trained doctors may not be allowed to work in the UK unless they spend several years retraining - and not always even then.

Sociological and economic differences causing immobility of labour

• Minority groups often get paid less. For instance, it may be harder for migrants who do not naturally speak English to find work and to receive the same pay. If they are not selected for a vacancy, it renders them less mobile. Even women, hardly a minority, find it hard to get the same pay as men, despite the existence of long-standing legislation.

• We can think of this as a lower demand curve for them, because employers do not like hiring them as much.

• Married or very close couples: one may not be able to take a better paid job offered elsewhere because it would render the other partner unemployed, so total family income would fall if they moved.

• The skills a person has may not fit the new demand for workers, so he or she would find it hard to get another job. As demands in society change (taste + higher

incomes + new goods + new technology + fashion and trends…) it means new skills are needed and old ones become redundant. How many chariot wheel makers do

we now need?

• Age: once past fifty years, or even forty years of age, it is difficult to get a new job.

Employers often prefer younger people. If an applicant is old, the employer fears that they will not learn new skills quickly; and if the applicant is older than the employer, he or she may feel uncomfortable giving them orders and so simply refuse to hire them in the first place; and old workers who join the firm will only pay into pension scheme for, say, ten years until they retire, but will take out for perhaps another thirty years until they die. An ageing population makes this scenario more common.

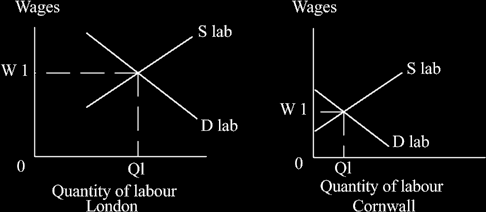

Such factors mean that wage differences (and unemployment) can permanently exist between industries and between regions. The market does not work well enough to equalise wages and long term wage differences persist.

Diagram: the wage of labourers in London and Cornwall: London has a greater supply but a much greater demand so the curves are further to the right. And of course in London, the level of wages and the quantity of workers are higher.

What can be done? Government intervention may help produce a better market solution.

Government training and retraining for the new skills that society needs.

The government may improve or alter the educational system and encourage academic courses to be more geared to the needs of a modern economy (although some intellectuals disagree and think education should not do this).

We can retrain workers at government expense. The state can pay for retraining courses and give generous tax breaks to those choosing to receive new skills.

The government may tackle the geographic problem

It may pay workers to move; or pay the costs of buying or selling the house; or end (or reduce) the stamp duty for such people; or pay the unemployed to travel to look at job opportunities in a new area.

It may subsidise firms to move to old decaying areas. This approach is generally inefficient, as it means costs will be higher than they need be, as it is probably not a good location for the firm (which we can assume or the firm would be there already or willing to go without a subsidy). This would make the UK less competitive with

other countries.

The government may allow pension mobility, i.e. when a person leaves a firm he or she can take their pension rights with them – the new stakeholder pensions do this. The push for people to take out their own private pensions means that workers are more mobile than they once were. There is a slight problem in that the rich who are usually already mobile are taking out stakeholder pensions, but the poor, less mobile, are tending to avoid them.

The government could change the laws as needed

Example 1. The government could make all company pension schemes pay out the employer’s contribution when worker leaves.

Example 2. The government could make the British Medical Association (BMA)

allow foreign doctors in to work more easily. The BMA is rather restrictive and keeps some well-trained foreign doctors from working in the UK unless they requalify or take special tests. This reduction in supply means there is a permanent shortage of doctors which helps the BMA to pressure the government for pay increases, better conditions, or whatever it wants.

Example 3. The government could pass “non ageist” legislation to try to stop older but good being refused jobs or even fired (government is planning to do this - eventually).

Other areas of law no doubt could be similarly changed – watch the newspapers for articles and examples that you could quote in the exam room.