| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Why Markets Can Fail | Reason 2 - Externalities, social.. |

Reason 2 - Externalities, social cost and private costs

EXTERNALITIES

Private costs are what they say – the costs incurred when producing something. Social costs are greater than private costs. Social costs include things like pollution

and congestion that are suffered by society in general, not by any one producer.

These problems are called “externalities” i.e., they are external to the firm producing them. They can be negative externalities (which harm society) or positive externalities (which help).

Social cost = private cost + externality (if any)

Cost-benefit analysis tries to measure all the costs to society of a project.

A new tube line in London may never run at a private profit but still generate large savings elsewhere. For example, the new line might reduce motorcar use, reduce congestion, speed up traffic flow, and save people’s time. The Victoria line, built

1968-71, was established knowing it would lose money - but the social benefits were so great.

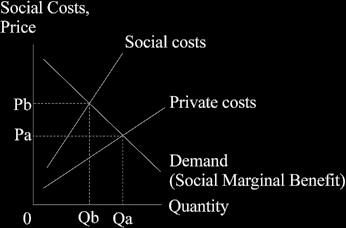

We have a diagram for social costs:

Equilibrium will be where private costs cut the demand curve at Qa, as firms try to maximise profits and charge price OPa for quantity OQa.

But because of negative externalities (pollution maybe), the socially optimum position should be where social costs cut the demand curve. These would mean producing at Qb, reading from the social costs curve, and selling at the higher price OPb to cover these costs.

NEGATIVE EXTERNALITIES

Common types of negative externalities by producers:

• Air pollution, e.g., smoky factory chimneys.

• Soil pollution, especially by farm chemicals (closely related to the next type).

• Water pollution, e.g., rainwater run-off containing farming pesticides and fertilisers.

• Noise pollution. Do you live near an airport or by a building site?

Some types of negative externalities by consumers:

• Pollution of air and water.

• Soil pollution, e.g., lead pollution in soils from motorcar exhaust emissions.

• Litter on streets; decomposing rubbish in land-fill sites.

• Noise pollution, e.g., motorcycle noise in urban areas, especially when the baffles have been deliberately removed from the silencer.

• Vandalism; graffiti on walls.

• Smoking and alcohol abuse, causing NHS expenditures to rise.

We are unsure why the urban sparrow population has plummeted in recent decades but it would seem to be the result of some externality.

POSITIVE EXTERNALITIES

When these exist, society would gain more than the producer – who therefore is producing less than the optimal social amount.

Examples include:

• Labour training in firms; one firm may do little, as it knows that when a trained worker leaves, someone else benefits - but the first firm paid for all the training!

• Education generally.

• Health generally, especially in poor Third World countries.

• The provision of playing fields at or near schools so that the health and sporting skills of the children improves.

• Free museums and art galleries that can encourage the poor and uneducated to widen their horizons, educate themselves, and generally improve.

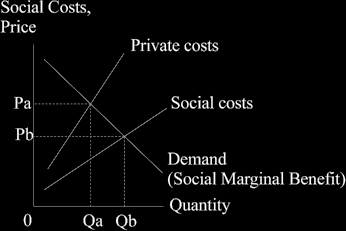

To draw the diagram for positive externalities: just reverse the labelling of the curves of social cost and private costs above. This is done in the diagram below where you can see that we produce too little for society if firms profit maximise for themselves (as they do). They choose to produce at OQa and sell for a price of OPa, but for the

greatest good of society they should be at OQb and selling at the lower price of OPb.

Government intervention may be necessary to correct or offset market failure caused by negative externalities – usually the government chooses to tax those producing too much, or they may use the law to prosecute for water pollution or whatever externality the government is tackling.

There are probably fewer cases of external benefits, but if we find any (such as private firms training labour well) we can encourage this by tax breaks or subsidies.

Government action with external diseconomies

Government might try (and does):

1. Taxation.

2. Regulation.

3. Perhaps extending property rights.

Let’s think about polluters – what can the government do using the three points above?

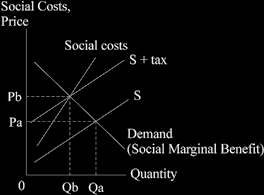

a) Taxing polluters

The need is to try to stop the problem being “external” and try to “internalise” it, i.e., to make the polluter pay for it via a tax. As economists, what we are really doing is trying to get the firm to stop looking only at the private costs and benefits. In the diagram below, we do this by putting a tax on, which shifts the supply curve up from “S Private costs” to “Private costs + tax”. If we get it right, this moves the equilibrium quantity produced from Qa to the smaller output Qb.

In the UK, we now have a Landfill Tax (since October 1996) to encourage recycling. Landfill operators have to pay a tax to the government. It was introduced at the rate for inactive waste, which is easy to deal with, of £2 a ton and other waste at £10 per ton. These amounts might increase shortly.

But there are problems with taxing polluters:

• When it works, output is reduced and prices are higher – but this can reduce the consumer surplus, which some feel is not a good thing (Unit 4 looks at this concept).

• It is often hard to identify the particular firms that are causing the pollution, and then determine how much each is responsible for the total pollution.

• Poor legislation can hurt the innocent, e.g. households who wish to get rid of large items of waste may not be allowed to take them to the dump.

• It is not easy to put a monetary figure on the damage pollution is causing.

• Producers can pass on much of the tax to consumers if demand is inelastic and not pay it themselves.

• Taxes on demerit goods (to limit their consumption) can be regressive, i.e., hit poor households the hardest. The tax on cigarettes does this because the poor are statistically more likely to smoke than the wealthier.

In the UK, the government quite regularly increases duty on petrol, & tax on cigarettes.

b) Regulating polluters approach (a second way that can be used in addition to tax)

• Banning cigarette advertising at sporting events, or in places like cinemas.

• Making workplaces no-smoking areas.

• Increasing the penalties for firms that break the regulations.

c) Extending property rights (a third way that can be used)

If a lorry crashes into your garden and destroys the wall and all your trees you can get compensation – but if a polluting factory puts out acid smoke and destroys the same trees you cannot.

If we extend property rights so you could sue for compensation, it would make the polluter think again and perhaps install anti-smoke devices on factory chimneys!

Benefits

• The property owner knows the value of the property better than the government does, so the figures will probably be more accurate (but owners can, and perhaps would, lie!).

• The polluter is forced to pay those suffering from his or her activities.

Disadvantages

• The damage may occur abroad, e.g., German acid rain destroys East European forests – but it is next to impossible to enforce law across borders!

• Global interests and national interests may conflict. The UK cannot make Brazil extend property rights over Brazilian trees which are being killed off at a rapid rate, yet the world might feel the destruction of the Amazon rain forest is wrong.

Trading permits to pollute

Many believe that it is so difficult and expensive to stop companies polluting (identifying who did it can be impossible e.g., with one stream and dozens of factories discharging into it) that instead we should auction off the right to pollute. Only those firms that pay a high price for the limited number of licences would be allowed to pollute. The government could then use the large sum of money raised to tackle the pollution itself. The end result could be much better than we currently have!

If we allow a firm to sell its right to pollute (it may have used only 80 per cent of what it is permitted, for example) then those with the greatest demand for their product, and hence the most profitable, can buy the remaining 20 per cent. It means the things we most desire still get produced but the government has the resources to tackle the resulting pollution.

Yet many think it is morally wrong to allow permits to pollute at all! Singapore uses such permits for ozone-depleting substances.

The Kyoto Summit on Climate Change (Dec. 1997) saw a move towards such permits as being an improvement at least! But the United States and Russia refuse to ratify this. In September 2004, President Putin of Russia agreed to it, but it still has to go before the Russian Parliament.

Coase’s Theorem

Ronald Coase established that there is no need to tax or regulate polluters at all! He saw that if polluters compensated those suffering, the market would solve it properly, with just enough “acceptable” pollution occurring and still no one suffers without being compensated. He got the Nobel Prize in Economics 1991 for this! It is worth trying to get the phrase “Coase’s Theorem” into an answer about how to deal with pollution.