| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Why Markets Can Fail | Economies of scale |

Economies of scale

What are they concerned with?

We look at what happens to costs as the size (the scale) of a firm increases; e.g., if a

firm grows by a given percentage, say 20 per cent, we examine what happens to the cost structure.

There are three logical outcomes if firm grows by 20%:

• Output grows more than 20% = economies of scale or “increasing returns to scale”.

• Output grows less than 20% = diseconomies of scale or “decreasing returns to scale”.

• Output just grows 20% = “constant returns to scale”.

NOTE it does not have to be 20 per cent – it is what happens to costs when the firm grows by any amount that interests us.

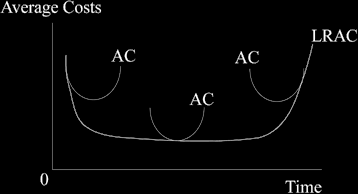

The Envelope Curve or Long Run Average Cost Curve

It often occurs that as a small firm grows, its average costs fall at first, then level out for some time, then finally start to rise. If we join up the tangents we get the “envelope curve” or the long run average cost curve (LRAC curve).

Digression:When drawing the envelope curve it is far easier to draw in the LRAC curve first, then fit the small AC curves to it. This is the reverse of the way we actually get the LRAC curve.

Remember that the average costs are always drawn U-shaped whatever the competitive state of the firm we are considering (perfect competition, imperfect competition, or monopoly). This helps you, because so you now know that you can always start your diagrams in the same way in all theory of the firm questions.

How can we get economies of scale? (“increasing returns to scale”)

1. Technical: a new machine can be used that reduces costs as output increases :

• Such a process is often referred to as “mass production”.

2. Financial:

(a) Banking:

• A large company can borrow at cheaper rate than others, e.g., Shell pays lower interest than I do to borrow money.

• When output is larger, it spreads the interest cost of borrowing over a greater number of units, so the average cost per unit is lower.

(b) Insurance

• A larger output again spreads the cost over more units.

• A large company may be big enough to do its own insurance and not have to pay premiums to others.

(c) Advertising

• Once more, the larger company spreads the advertising cost over more units.

(d) Purchasing

• Bulk buying is cheaper.

3. Managerial

• A large firm spreads the cost of management over more units.

• Management may be underused in small firm.

• In a large company the managers can specialise: there might be a marketing manger, a transport manager, a production manager and so on - each does a better job as a result of specialisation..

4. Risk spreading

• A large company can have a greater variety of produce - if the demand for one product falls off, the demand for others will probably be still be good.

• A large company can sell in different markets, perhaps including several export markets.

• The firm’s own insurance can be done (already mentioned).

Note: cost curve eventually turns up at the right hand end. This reflects

diseconomies of scale, or decreasing returns to scale

Q. Why does it turn up in this way or why do they occur?

A. There are three main reasons:

• Managerial limitations

• Financial factors.

• Quality deterioration.

1. Management. This is the most important reason usually.

Management becomes a fixed factor in a sense. The firm gets too complex for one person to manage everything, mistakes are made, and decisions are slower causing costs to increase.

A firm can increase the number of managers to offset this diseconomy and perhaps put it off until a larger output is reached - but as managers increase in number we can expect to see new problems arising.

• Red tape arises, that is to say, there is a slow and cumbersome bureaucracy.

• Meetings proliferate and a paper war starts.

• Factionalism arises, each department starts to try to score off others and do them down. This is often an effort to advance one’s self in the promotion race but some people simply develop a loyalty to their own division and start to dislike other divisions.

• A new idea of safety and security arises. The new managers tend to be administrators with less entrepreneurial skills,and they also try to protect their backs rather than promote the interests of the company.

• A new breed of people, "corporation people" emerge – the firm is no longer chasing profit and taking risks but coasting along.

• Communications falter, up and down as well as sideways. People do not all know what is going on.

Some things may offset the managerial diseconomy:

• Computers and technological progress, e.g., photocopying machines speed up the paper chain (although they increase its length!)

• Various incentive and bonus schemes are possible, including stock purchase options (mostly for managers who can later buy shares in company at a price agreed now. It means that if they work hard and the company makes profits, the share price will rise, and they can buy cheaply - so they get rich).

• Bonus may be linked to growth in profit level, for workers or managers.

• No absenteeism or unauthorised sick leave by a worker for a defined period of time may attract a bonus. British Airways were considering this in 2004.

• Possibly a person might receive a bonus if he or she is never late for work for a defined period (this applies to lower grade workers more often).

• Suggestions boxes, meetings to invigorate staff, etc. might be used and can help to some extent.

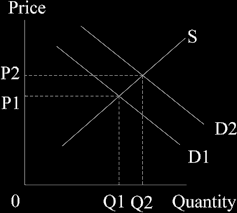

2. Financial diseconomies may arise:

As a firm grows, it increases its demand for everything, including perhaps some particular factor of production, a needed raw material, or certain spare parts. As demand increases it can turn the price up against itself (an increase in demand with normal supply curve; we will look at the diagram again later on).

3. Quality diseconomies may occur:

When a firm starts up, it hires the best labour it can find, and buys from the best source of materials available; but when it has taken all that is possible from these sources, to grow further it may be forced to:

a) Hire lower quality labour, which will mean a lower productivity.

b) Take worse raw materials, or hire less suitable transport vehicles (say, not well refrigerated) because the really good ones have already been taken and there are none of comparable quality left available.

And both these actions will increase the firm’s costs of production.