| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Managing the Economy | Fiscal policy |

Fiscal policy

Why the government raises revenue through taxation:

• To cover its expenditure.

• To redistribute income, usually from the richer towards the poorer.

• To reallocate resources.

• To change consumption patterns (reduce cigarette consumption?).

• To control the economy (our main interest here).

As you know, there are two major policy instruments available to control the economy:

fiscal policy and monetary policy.

The government uses these to try to alter level of national income (GDP), from where we think it currently is, to where the government would prefer it. (Because of time lags in

the data, we are never really sureexactly where we currently are!)

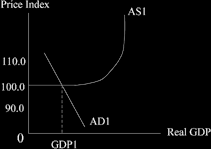

Here, the level of GDP may be thought too low, so the government may wish to increase aggregate demand and “fine-tune” the economy.

What is fiscal policy?

Fiscal policy means the use of taxation (and maybe a few subsidies which are a sort of

“negative tax”) to alter the level of aggregate demand.

Fiscal policy aims at consumption (C) and/or investment (I) and or government (G)

G is not easy to turn on and off for fine-tuning purposes. The government is unable to reduce pensions by fifty percent in order to reduce its total expenditure! Nor can it

suddenly stop building a motorway which is ninety per cent finished. In other words, much of government expenditure is not really discretionary at all.

Changes in government expenditure are generally thought of as part of fiscal policy; otherwise we have to see it as “direct government intervention”. Some textbooks may call it that or use a similar phrase like it.

If the government wishes to increase the level of GDP is means reducing some tax rates, or perhaps abolishing some tax completely, in an effort to increase C or I.

Fiscal policy can also have a strong affect on income distribution. The main aim of any government here is to redistribute income towards those who are felt to be deserving. These are often the poorer, but groups like farmers in all developed countries and, under President Bush the oil producers in the United States, seem quite adept at getting income to move their way.

What taxes has the country got?

This is purely descriptive stuff! I suggest you read it up for yourself in the latest textbook and keep you eyes on what is in decent newspapers. Each country is very different and changes its tax system quite regularly. Few books can be up to date.

A bit of fiscal detail:

A “direct tax” is placed on directly on people or companies, e.g., income tax, company tax or a capital gains tax, and such taxes can be hard to avoid. In principle they should be impossible to avoid, but in practice the rich and the powerful trans-national corporations can often minimise the tax they pay and that to a rather surprising extent.

The other type of tax is an “indirect tax” Indirect taxes are mainly placed on spending; this means that if one does not buy the item, then one does not pay the tax, i.e. it is something of a voluntary tax! In the UK, value-added tax (VAT at the standard rate of

17.5%) is well-known; but we also have “duties”, such as the tobacco tax and the excise duty on alcohol.

To increase the level of aggregate demand the government could reduce the rate of any or all taxes, like VAT, income tax, corporation tax etc. But such a change is normally only done in the annual budget, or sometimes in a mini-budget around October, half way through the fiscal year. So if we are considering the timing, fiscal policy is not very flexible! Monetary policy can be altered at any time, although if interest rates are altered it will normally be on the first Thursday of the month.

Direct versus indirect taxation

Direct tax:

• This can reduce the incentive to work if it is set at high levels (the view of Prime

Minister Thatcher and President Reagan).

• A direct tax can be legally avoided although this can be quite difficult (taxevasion is always illegal).

• A direct tax, like income tax, can be made progressive. This means that we can tax the rich proportionately more than the poor. On paper, income tax may look

progressive but in practice it is often not so. Income tax is easily and legally avoided by the really rich, but the poorer and those in the middle are forced to pay. For really rich people, income tax appears to be rather regressive.

Indirect tax:

• This is seen as regressive as it can hit the poor more than the rich because it is a higher proportion of their (low) income. The poor also tend to smoke more than the rich, so the tobacco tax seems particularly regressive.

• One can avoid paying an indirect tax if one does not buy the item, e.g., as a reformed smoker I no longer pay tobacco tax or the VAT on cigarettes.

Fiscal changes can strongly affect the distribution of income; monetary policy changes affect the distribution of income less, because they are as more general in impact.

How the government might increase the level of national income by lowering tax

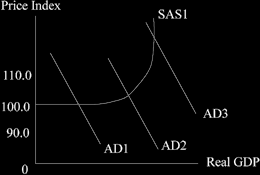

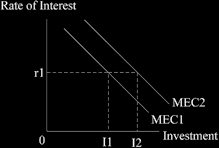

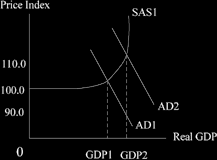

The government might choose to reduce, say, the level of corporation tax, in an effort to encourage business optimism. This could shift the marginal efficiency of capital curve to the right and thereby increase the amount of investment undertaken. The increased investment would then cause gross domestic product to rise. (See the diagrams below).

Pushing out the MEC curve

The government is aiming at increasing the “I” part of C + I + G + X – M

The increase in investment pushes up the aggregate demand curve and real GDP increases.

If the government were to reduce, say, the level of personal income tax, it is aiming at the

“C” part of aggregate demand.

Automatic stabilisers

Automatic stabilisers are built into the system and modify its effects – they work a bit like a thermostat in a central heating system. Automatic stabilisers do not require government action or initiative; they just come into play naturally. An example is progressive income tax - any increase in income is moderated, because the tax automatically rises as income increases.

Automatic stabilisers can help counteract the ups and downs of the business cycle. They cannot prevent swings, but they do moderate them.

A FEW POINTS YOU SHOULD KNOW

PSNCR = the “Public Sector Net Cash Requirement” which is the difference between government spending and tax revenue.

Government sells bonds in order to raise money to cover the PSNCR; but to do this it will need to raise interest rates to attract more bond buyers. Raising interest rates can make private investment more expensive so it can get crowded out!

If revenues are greater than expenditures, we have a surplus, which can be used as a “Public Sector Debt Repayment” (PSDR) to buy back government bonds and reduce the level of national debt.

What determines if there is a surplus or a deficit?

• The part of the trade cycle we are in. During a boom, government revenues are high (the receipts from income tax and some other taxes increase); and on the expenditure side, payments of social security benefits will be lower. Both these factors mean we can see a surplus.

• The passage of time – government spending tends to increase over time.

• Changes in the political demands of the people. If people want pensions to be higher, unemployment pay to be greater, and/or family benefits to be improved, this will lead to more expenditure. A deficit is then more likely.

• Government attitude – if the government wants more investment for future growth, it might try to cut PSNCR as this would help to keep interest rates down. (If the government borrows it has to increase the rate of interest which reduces private investment; as it is trying to encourage investment, the government may try not to borrow).

NB Fiscal policy is the only onedirectly available to the government now. You will recall that the government gave the right to run monetary policy and set interest rates to

the Bank of England in 1997.

Some problems of using fiscal policy

• The measures adopted may not be in line with the Bank of England’s monetary policy measures.

• Fiscal changes are only undertaken once a year in the budget – inflexible. There may be leaks in advance of what the government will be doing in April next! At best we can have an extra “mini budget” around October to improve flexibility.

• We cannot easily stop and start government spending – takes years to plan and push through a motorway for example; social services expenditure is not easily reduced (very unpopular!)

• We are not sure where we are and sometimes are uncertain as to what direction we should be aiming for (should we increase or decrease GDP?) because of data and other lags. This applies to monetary policy too.

• Government can be bound by its earlier promises, e.g., the current Labour Government promised not to increase income tax rates. It is difficult to use fiscal policy if one is not allowed to increase taxes!

• This throws the burden of adjustment entirely onto monetary policy– and it is in the hands of the Bank of England rather than the government itself.

• The desire for fiscal harmonisation within the European Union may mean that tax rates will be controlled in Brussels in part or whole at some time in the future. This would reduce our power to use fiscal policy.

• There is an old question of whether or not high income tax is a disincentive to work harder or longer. If it does act as a disincentive to effort, we know that tax rates have been reduced in recent years, so we should have seen an explosion of new effort. Have we? Casual observation suggests that it has not, so perhaps there is no strong disincentive.

• Accurate prediction of deficits and surpluses in the budget are very hard to do!

• Altering the level of tax may sometimes lead to unwanted redistribution effects.

• Unpopular fiscal change can lead to a fall in business confidence which could cause a reduction in investment and almost certainly alter the assumptions upon which the original fiscal change was based!

• Borrowing to meet a deficit can crowd out private investment (reducing growth; changing the framework within the government was working; and almost certainly altering the assumptions within which the borrowing was to occur).

NB there has been no real test of fiscal policy since the government gave away its power over monetary policy as the economy has grown reasonably steadily and well. The crunch is yet to come. Only when a system is put under pressure do the hidden weaknesses emerge!

3-10. ALTERING THE AGGREGATE SUPPLY CURVE

A quick reminder: we always start in equilibrium in economics. Then we alter something, usually we shift a curve which reflects some real change that has occurred, and see what the result is.

When we are looking at the macro economy and national income, we have three choices of the equilibrium in which we may start: recession, full employment, or in between .