| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Labour Markets | Labour participation, unemployment.. |

Labour participation, unemployment and ageing

The labour participation rate

The Labour participation rate is the proportion of the population between 16 years of age and the retirement age (currently 60 for women, 65 for men) who are in work or who are unemployed but wish to work and are actively seeking work. The figure has recently risen to 75.5% of the UK population (2004) and the figure is expected to continue to rise over the next few years.

Those not in the group (i.e., are economically inactive) consist of:

• those not wanting a job;

• students;

• those looking after a relative or family at home;

• the long-term sick; and

• the retired.

When unemployment is high, the participation rate tends to fall, as people feel discouraged and stop looking for jobs because they are aware that there are few or none locally. Unemployment is currently low so the participation rate is high.

Unemployment: what it is and how it is measured

• This was covered in Unit 3-3.

The changing labour markets – some points you might find useful

• Advances in new technology are rapid, which means that new skills are constantly needed. The computing and information technology areas are particular examples. This is a supply side led change.

• There is changing demand for new products, for instance some people constantly demand the latest mobile phones with special features. This is a demand side led change.

• The developed world generally has high labour costs when compared with developing countries. Many manufactured goods can be made labour intensively or capital intensively and are much cheaper from, say, China which is a low wage country. This means we tend to import more manufactured goods over time and so domestic

manufacturing industry declines steadily. This means that old skills are less needed and some are not needed at all.

• Geographical location of the old manufacturing industries. These are often in the north or the midlands which means a localized unemployment problem of people with the “wrong” skills exists and persists.

• The weakening of trade unions since 1979 means that it is easier for workers to:

o move from one job in a firm to a different type of job in the same firm;

o move to new occupation, as many restrictive rules that prevented entry have been relaxed.

• Entry into the European Union has meant easier worker movement and migration within Western Europe. Labour markets are much more flexible now than in the

1970s.

An ageing population

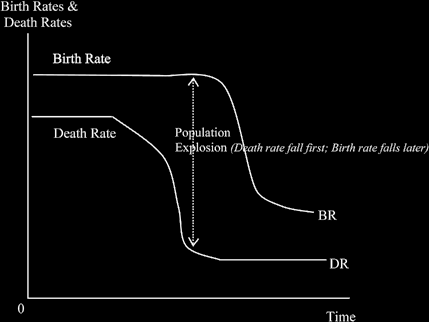

All developed countries are similar: they register a low and falling birth rate and a falling death rate. Developing countries on the other hand often have a high birth rate and

falling death rate, so their populations increase rapidly.

There is a lot of evidence that over time, countries start by reducing the death rate, get richer with economic development, and the birth rate eventually falls. But before that happens there is a population explosion. By now, the developed countries, like the UK, have come out the other end and so have slow growing populations. In some cases population is static or even falling, like in Italy. The Asian Development Bank forecasts that even countries like China, Singapore and South Korea will have declining populations by the middle of this century.

Population movement over time

Countries start with high birth rates and high death rates – which means population increase is slow. If you forget which one goes on top, think! We know that the birth rate must be above the death rate or everyone would be dead before now!

Then the death rates start to fall, and fall sharply, as a result of better public health facilities, improved hygiene, more and better doctors, and advances in medical technology. This is the period of population explosion. Many third world countries are in this period today.

After a lag, birth rates start to fall. As people become richer they seem to prefer smaller families and in addition, contraception becomes more easily available as countries develop and it becomes more widely adopted in the society. This situation is typical of a

developed country, with low death rates and low birth rates, and little if any population increase.

The low birth rate and slow growth of population ensures that we have both an ageing population and a greying population in developed countries. This has several consequences:

• Changes in the demand pattern – society needs more wheelchairs, Zimmer frames, retirement/nursing homes and hip operations but fewer prams, baby clothes or primary schools.

• A slowing down in labour mobility – this tends to lessen, as old people are often less willing to move than youngsters.

• Changes in demands on government – in particular there is an increase in the need for higher and higher expenditure on pensions and health care. This is a serious problem; the government needs to raise more money in total or else it may eventually have to reduce the quality and quantity of pensions and health care.

• In 1950 a man retiring at age 67 (the average age at that time) would have reasonably expected to live for only eleven more years; in 2004 the average age of retirement was 64 and the man can expect to live for a further twenty years,

almost twice as long.

• Reducing the standard of pension provision and health care would carry with it the danger of social and political backlash. For such reasons, the governments in developed countries, like the UK, are trying to make workers save more for their

own pensions. An effort is being made to move society away from the approach of expecting cradle-to-grave social security to looking after one’s own old age.

• Change in the participation rate – we will see fewer workers available to take care of the steadily increasing number of dependents (the elderly) because of the population pyramid and the genera ageing. This means there will be a smaller tax base yet higher demands for tax revenue to meet the growing demands.

• Britain has a serious problem here but because of demographics and the higher pensions paid in most of the rest of Europe, we are better placed relative to the other European countries in one respect – their pension burden demands will be higher than ours in the future.

A reminder: are you revising something and practicing drawing diagrams each day? If not, go on, have a go at it, starting now!