| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Labour Markets | Differences in earnings |

Differences in earnings

The reasons for different wages in different occupations are always:

1. Different supply and demand situations; or

2. Market imperfections; or

3. Non-monetary rewards.

1. Different supply and demand for different occupations or regions

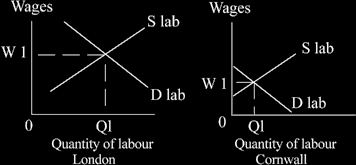

If we look for example at the wages of manual worker wages in London and Cornwall, we find that in London the supply of and demand for manual workers are both greater, but in London the demand is relatively greater than supply. It is no surprise that the wages in London are higher.

Notice that the supply and demand curves for Cornwall are well to the left when compared with those for London. Cornwall has a small population.

The same analysis holds for many earning comparisons, such as:

• why doctors are paid more than nurses;

• why general practitioners earn less than brain surgeons;

• why the earnings of financial analysts in the City of London are greater than those of super-market check-out staff; and

• why a few star sports earn more than almost everybody!

There are many possible questions about why group X earns more than group Y, but they all require the above diagram and general approach. It is a supply and demand situation.

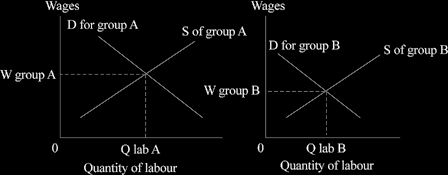

This approach can also be used for analysing differences in wages among different social groups:

If the dominant group (A) does not like members of the other groups (B), when members of the A group are hiring labour, they are more reluctant to take on members of the B group. This means that there is really a different and lower demand curve for the labour of the B group, which means they are both employed less, and where it is allowed, they will be paid lower wages.

[This can be a difficult topic to discuss as we are talking about real people with perceived or actual differences, and we are all human beings. Antagonism is easily aroused and tempers might fly. If you have to discuss such issues I can only suggest you take great care.]

Group A (B in brackets) can represent any number of people:

• White skinned (v. non-whites) [racial prejudice in white society].

• Chinese (v. West Indians) [a particular antipathy, perhaps against the gangster

Yardies, perhaps because of skin colour or other reasons].

• Males (v. females) [the “glass ceiling”].

• Southerners (v. Northerners) and vice-versa [geographical cultural bias].

• Public school accent (v. local accent) and vice-versa [class war].

• Christians (v. Jews) [a 2000 year history].

• Christians or the non-religious (v. Muslims) [especially since Sept. 11th but cultural prejudice goes back at least as far as the crusades of the 11th-14th centuries).

• Skilled workers (v. unskilled).

The analysis can be applied to any group that can be more or less identified about which people have prejudices in fact. NOTE: This is NOT to condone such prejudices.

The concept of “non-competing groups”:

These are people who do not compete for the same jobs. As an example, shelf-stackers in supermarkets do not directly compete with GPs, so if the earnings of GPs increase substantially, shelf-stackers do not pour into medical schools.

It is believed that the competition does work, but indirectly through a ripple effect; as a simple example, students who might have gone into teaching opt for medical school, some people who might have found work directly from school decide to go to university and become teachers instead, and some shelf stackers take the jobs thus “vacated”. The ripple effect is probably much more complex and can be slow, but the general idea is clear.

2. Market imperfections, another reason why supply and demand may not work perfectly

• The laws of the state may prevent it. An example is minimum wage legislation that raises the wage for some but an unintended consequence is that it may prevent really poor people from ever getting a job (we consider the national minimum wage below).

o (Government response: they might change the law but this is unlikely).

• Trade union restrictions on supply (see above).

o (Government response: they have tried to weaken the unions).

• Union attitudes about maintaining wage differentials. A union might try to ensure that a clerk gets a wage twenty-five per cent above a cleaner; if cleaners get a rise, the union might demand and obtain an increase in the clerk’s wages to maintain the differential. These established differentials often seem to reflect the demand and supply situation of long ago.

o (Government response: they have tried to weaken the unions).

• Monopsony which means a sole buyer. If there is one huge employer in a town, s/he may be able to exploit workers by paying less than the marginal revenue product (see the analysis and diagram below, p.225).

o (Government response: a national minimum wage).

• Time lags. We may never get to the equilibrium before it changes again.

o (Government response: it can do nothing much – it might try telling people more quickly about changes, or speed up the workings of the bureaucracy if it can).

• Labour immobility.

o Economic: where the local demand for skills does not meet the supply of skills. There is a strong need for information technology people in the South- east and yet we see unemployed coal miners around Nottingham.

- (Government response: to retrain workers in new skills; they could also give a worker money to live on while retraining and finding a new job; subsidise moving expenses; subsidise house sale and purchase, perhaps guarantee no loss on this).

o Geographic:

People frequently do not know about jobs elsewhere (knowledge is sometimes listed as a separate reason, with a cost involved of obtaining the information needed).

People will not give up a cheap council house with low rent.

And selling one’s home and buying new one elsewhere is expensive.

- (Government response: they can tell people more about opportunities in other parts of the country; improve job centres; advertise on TV; and make council house swaps easier. Some are allowed but they are hard to achieve - we could set up a national centre to list them all).

o Social:

Existing pension schemes may tie workers to their current employer. They have family nearby and not wish to leave them.

Social groups, their friends, the clubs of which people are members all tie them to an area. Racial or religious ties to an area are common too.

- (Government response: not a lot they can do?)

3. Non-monetary rewards

The idea is that some jobs pay less because they are so nice to work in that workers will take a lower wage – they used to say this about teaching! Now teaching still pays less and is widely believed not to be a particularly nice job!

It is, in my view, a suspect argument – the best paid jobs also tend to have the best non- monetary rewards, like one can take time off easily, or enjoy good working conditions. People like barristers, accountants, or economists are usually better paid and have good conditions when compared with agricultural labourers, or conveyor-belt workers in factories. I have done both these latter jobs and I know of what I speak!

The National Minimum Wage

The idea is that there should (normative!) be a minimum wage below which no one should have to work. At first sight it certainly seems to be a good social idea, but the economics are a bit more dubious.

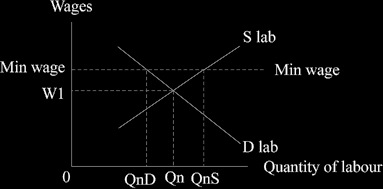

The diagram is the standard one for price setting, such as we would find for tomatoes. If we raise the wage above the equilibrium level, we will get excess supply of labour and some unemployment.

• The market solution would be at wage level W1 & employment at Qn.

• With a minimum wage we contract up the demand curve for the demand for labour, and at the same time extend up the supply curve for the change in the quantity of labour supplied. The result is:

a. Wages rise to the level of the minimum wage.

b. Employment falls to QnD, reading off the demand curve for labour.

• Compared with the competitive equilibrium solution there are fewer in employment, but those who do get a job have a higher income. Which is the better situation is an ethical/social question to which economics cannot provide an answer.

Caution - this is a micro diagram but dealing with total unemployment is a macro issue. Unemployment can be tackled more generally as we learned in Unit 3.

There is one time that a minimum wage works well - monopsony:

If a small town has a monopsony employer (the only large company in town) who is exploiting labour locally by paying a low wage, imposing a minimum wage can help. Perhaps surprisingly, it would mean that the employer would not only have to increase wages but also the monopsonist would choose to employ more people.

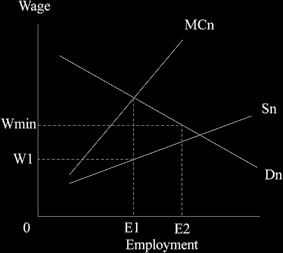

The monopsony diagram.

With a monopsony, when the firm hires an extra person it can turn the price up against itself and if the supply curve is normal (as it almost certainly will be), this is going to happen.

The argument is that if the employer pays the next person employed an extra £5 a week in order to attract them, he or she has to pay all the existing workers an extra £5 too, or there will be labour strife. So the marginal cost of one more worker is a lot more than £5! Thus the marginal cost of workers (MCn below) is above the supply curve. The firm selects the number of people to be hired on the basis of MCn but only has to pay on the basis of Sn! The result is that a monopsonist pays a low wage and hires fewer workers.

Before the imposition of a minimum wage, the employer chooses to hire E1 (the intersection of MCn and Dn) and pay W1 (the amount needed to get E1 workers, reading off the supply of labour curve, Sn).

The introduction of a national minimum wage, such as Wmin (which reads straight across to the demand curve Dn), will increase wages from W1 to Wmin and increase employment form E1 to E2.

Unemployment pay

Many economists believe that when the state gives unemployment pay (social benefit etc., as part of social services) this increases unemployment by allowing people not to work! It is probably true – it is reasonable to think that the normal supply curve would work. Offering more and more money to the unemployed could be expected to attract more people to give up.

For £2,000 a week I would love to stay home. However, at the relatively low sums offered in social benefit to the unemployed, it may only attract small extra numbers, so it is the size of the response at the going rate that matters rather than the principle.

The effect may not matter much, if relatively few are tempted into long term employment. It would matter if a lot are so tempted! Political prejudice is rife on what people believe here. Labour supporters tend to think either there is no effect or if there is one it is small; conservative supporters tend to think it exists and it is large.

There is one major gain for society when offering money to the unemployed. This is known as “search time”. This argues that there is be a benefit for society if a person can stay out of work, with unemployment pay, for a few weeks until he or she finds the most suitable (higher productivity, best resource allocation) job. Without the money, the person might be forced to accept the first job, or one of the first jobs, offered, however unsuitable. It is far better to wait for a few weeks in order to obtain a position that really suits the skills and ambitions of the person.

Many years ago I was personally unemployed for some weeks after I left the British army. The first and only job I was offered by the state unemployment office was sticking up movie posters on billboards. The fact that I suffer from vertigo meant that this was a totally unsuitable job for me, but it was still offered! I turned it down and went back into education instead.

The search time argument is a decent defence of unemployment pay – but again, we are unsure what numbers are involved.