| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Globalisation and Protection | The balance of payments |

The balance of payments

This was introduced in Unit 3but I repeat a bit here, then expand it to consider how we can deal with problems in it.

• What is the balance of payments?

The balance of payments is a record of a country’s economic transactions with other (foreign) countries. It includes the trade in goods and services, reveals how we pay for this, or if did not pay it tells us what we still owe. It also includes other financial flows, like foreign investment and company dividend payments.

We used to consider the balance of payments was divided into two: the current account and the capital account. In 1998 a new method of presenting our international situation was introduced which contains four categories within the balance of payments.

1. The current account.

2. The capital account.

3. The financial account.

4. The international investment position.

THE CURRENT ACCOUNT

This course focuses heavily on the current account, which includes:

• Trade in goods.

• Trade in services.

• Income from working abroad, and from investments abroad.

• Current transfers: central government and private.

The UK Balance of Payments, 2003 in £ millions – The Current Account (Simplified)

| CREDITS | DEBITS | BALANCE | |

| GOODS | |||

|

10,827 | 21,099 | -10,272 |

|

3,325 | 6,125 | -2,800 |

|

16,478 | 11,128 | 5,350 |

|

54,244 | 55,751 | -1,507 |

|

101,961 | 138,255 | -36,294 |

|

868 | 1,594 | -726 |

| Total Goods | 187,703 | 233,952 | -46,249 |

| SERVICES | |||

|

11,424 | 16,679 | -5,255 |

|

13,673 | 29,443 | -15,770 |

|

13,244 | 3,277 | 9,967 |

|

49,965 | 25,060 | 24,905 |

| Total services | 88,306 | 74,459 | 13,847 |

| INCOME | |||

|

1,116 | 1,059 | 57 |

|

125,250 | 101,922 | 23,328 |

| Total income | 126,366 | 102,981 | 23,385 |

| CURRENT TRANSFERS | |||

|

4,173 | 10,942 | -6,769 |

|

8,886 | 11,860 | -2,974 |

| Total current transfers | 13,059 | 22,802 | -9,743 |

| CURRENT ACCOUNT TOTAL | 415,434 | 434,194 | -18,760 |

The Ten Economic Goals and the Effects on the Balance of Payments

| WHAT MIGHT OCCUR | THE EFFECTS WE MAY EXPECT TO SEE |

|---|---|

| If we grow faster. | The B of P worsens, as growth sucks in imports to sustain production + higher incomes mean consumers buy more foreign goods and services (these are generally income elastic). |

| If the standard of living rises. | The B of P worsens as consumers buy more foreign goods/services. |

| If resource allocation improves. | The B of P probably improves, as the country is doing what it is best at. |

| If income distribution becomes more equal. | The B of P probably improves, as the rich reduce their purchases of foreign goods/services but other incomes will not rise enough to suck in many more imports. |

| If inflation increases. | The B of P worsens as our exports fall and imports rise. |

| If unemployment increases. | The B of P is probably a bit better as incomes are lower, which means consumers demand fewer imports. |

| Value of currency changes. | If the pound gets weaker it encourages our exports and discourages imports, so the B of P probably improves. Note that the currency may be weak because the B of P is already poor! |

What can we do if the balance of payments gets into a “fundamental disequilibrium” state?

A fundamental disequilibrium state means that:

• imports are considerably more than exports; and

• there is a persistent balance of payments deficit; and

• there is no likelihood that this situation will change.

The IMF will only allow major changes in exchange rates or special action to help the balance of payments if the country can persuade the IMF officials that there actually is a fundamental disequilibrium.

There are three possible ways of tackling this:

1. Via the exchange rate system – if the exchange rate is fixed (like China which currently fixes the yuan against the US dollar) we might alter our exchange rate

(although countries are bound by the IMF agreement as long as they are members. This solution is not applicable to the UK as our exchange rate floats (see below).

2. Via demand side management of the domestic economy. Lowering the level of aggregate demand would provide short term help by reducing imports and possibly freeing up some goods and services for exports.

3. Via supply side management of the domestic economy. Pushing out the long run supply curve would provide permanent help.

The first way of tackling a balance of payment problem: changing the foreign exchange rate

The exchange rate methods that a country might have adopted

1. Floating.

2. Fixed.

3. Managed.

1. Floating rates:

These are normal for most countries these days; floating rates are currently in force for the UK.

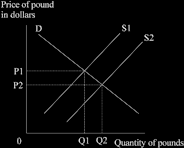

The supply of and demand for the pound determines its value.

1. The demand for pounds comes from foreigners who wish to buy British goods or invest in Britain.

2. The supply of pounds comes from the British, as we buy goods or services from abroad or we send money abroad to invest there.

This is the normal supply and demand curve situation: if we increase our imports, the supply of pounds increases, so the value of the pound starts to fall.

When this happens, a second element might swing into action. Speculators might jump in and sell pounds, hoping the fall will continue so that they will be able to buy them

back later at a lower rate. Should speculators sell in this way, it will drive the pound even lower.

2. Fixed rates (the regime a country might have adopted):

The government sets the value of the currency in the foreign exchange market. It is usually set well out of line with the foreign exchange rate that the market would determine – there is no point otherwise because it can simply be left to the market This method is not used much, except by a few communist countries.

Linking the rate to another country fixes it in a kind of way, but as the value of the other country’s currency alters, so does yours! Malaysia currently links to the US$ which helps it to stabilise its export and import prices for the USA and set them for other countries in international contracts.

With our floating rate: if the balance of payments deteriorates, the foreign exchange rate worsens automatically – thus making our exports cheaper and imports dearer, so it should automatically correct the imbalance in time.

With a fixed FX rate: with “a fundamental disequilibrium” the country could devalue – if the IMF will let it! Secret meetings would normally be held and the government would try to persuade the IMF officials that there really is a “fundamental disequilibrium”.

A small digression: what can affect the balance of payments (and hence the value of the currency)? (Note: you may need this for the exam).

1. Our demand for imports.

2. The demand of others for our exports.

3. Our inflation rate compared with that of others.

4. Our rate of interest compared with that of others.

5. Speculative capital flows.

Our demand for imports: if we import more, the balance of payments on current account weakens and pounds flow abroad. This increase in the supply of the pound reduces its value. The normal supply and demand curve analysis applies, as in the diagram above.

The demand of others for our exports: if foreign countries increase their demand for our exports, our balance of payments improves and the value of the pound rises. The other countries demand pounds in exchange for their currency, as they have to pay us in pounds in the end.

Our inflation rate compared with that of others: if other countries inflate more slowly than we do, our exports become relatively dear (so we can sell less), and our imports become relatively cheap (so we import more), with the result that the balance of payments deteriorates. This causes the pound to fall in value. You can see that when we pay for the extra imports it puts more pounds on the market, while selling fewer exports means we earn less foreign exchange.

Our rate of interest compared with that of others: if our interest rates rise (and no other countries match it) then foreigners send more money to us to earn a higher rate of interest and hence a bigger income. The influx of foreign capital then increases the value of the pound and strengthens the balance of payments.

Speculative capital flows: “hot money” can race around the world seeking the highest rate of interest commensurate with safety and risk. As the world gets wealthier and multinational corporations increase, the size of the flow gets larger. If hot money races into a country, it strengthens the balance of payments and increases the value of that country’s currency. The real danger will come later when it races out again! The value of the currency could then fall sharply and the balance of payments could weaken rapidly. The total effect can be very destabilizing. The IMF will usually lend money to help a country offset the sudden flood out.

3. Managed rates of exchange (the regime a country might have adopted):

This system is much like the floating one. The difference is that the value is not completely free to move for ever. The government may step in (should it feel like it) to shore up the foreign exchange rate if it starts to fall. It does this by buying pounds, using

the foreign exchange and gold reserves to do so. If the value of the pound begins to increase, the government may judge it right to step and moderate the increase by selling pounds on the international market. This would then increase the foreign exchange reserves.

Although Britain has a floating exchange rate system, in the past the government has been known to intervene to protect the value of the pound by buying and selling foreign exchange. The rate of interest set by the Bank of England also affects the value of the currency, as you will recall, because relatively high rates of interest attract foreign money to be placed on deposit here. The government is influential in deciding on what rate will be set. We know how the voting on the Committee went but the internal arguments are normally secret.

The second way of tackling a balance of payments deterioration: demand side management

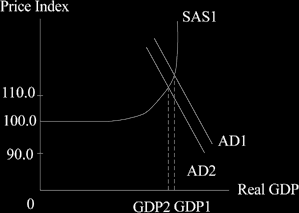

Reducing the level of aggregate demand can have a short term effect and help the balance of payments.

If we see the balance of payments weakening, perhaps because of high levels of domestic consumption and imported consumer goods, the government can reduce the level of aggregate demand, take the heat out of the economy, slow growth or even reverse it, increase unemployment, and reduce inflation. This will help the balance of payments by reducing imports and also by releasing goods for export that are no longer consumed

here.

Generally, this would be a short term response to a sudden crisis – the government chooses to squeeze the economy because too much is going wrong within the ten goals.

The third way of tackling balance of payment problems: supply side management

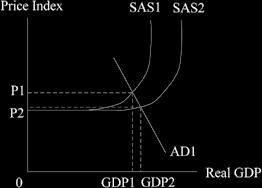

Changes on the supply side tend to be a long term thing and it is not a tool that can suddenly be wielded in a crisis to give quick results. It is a theoretical possibility but a nation is usually well advised to keep trying to push out the supply curve anyway as part of an ongoing process.

If we can increase the long run aggregate supply curve (the vertical part of the SAS curve) it pushes down prices as well as increases output. This means our exports get absolutely cheaper, so we are able to sell more, and hence the balance of payments will improve. We also import less because our imports are relatively dearer now when compared with home produce.

Here we see the SAS curve moving to the right (an increase in the underlaying rate of economic growth) and gross domestic product increasing.

Other than the initial increase in growth and the improvement in the balance of payments, we would see benefits for some other goals too: there would be an increase in the

standard of living (as prices fall and as incomes rise); and we can also expect an increase in the number of people employed.