| Home | Revision | A-Level | Economics | Globalisation and Protection | External shocks and the.. |

External shocks and the global economy

All large shocks have an impact on the world level of economic activity, e.g., higher oil prices; the war in Iraq in March 2003; or the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

All questions about external shocks can be tackled in the same general way:

1. The impact of the event on the ten major economic goals. (You will need to think about them and apply them to your particular case. If you jot all ten down, say in the margin of your exam question paper, you can ensure that you do not miss any out).

2. The transmission of the event and its consequences around the world, which is greater and faster than it used to be as a result of globalisation. Remember that the exports of one country are the imports of another. The flows of liquid capital might also be affected. Naturally, some countries will be affected more than others.

3. You can almost always use the diagram of the determination of national

income by means of aggregate demand and supply to show the domestic effects of any major external shock.

But clearly there will be differences in what will happen and not all events have exactly the same results.

You might be asked about the effects on the UK specifically, or the question could be more general and concerned with the effect on a wider area; always tailor your answer to the question asked.

As an example, let us examine the effects of the current war in Iraq following the invasion by British and American troops on our national economy.

• All wars increase the level of aggregate demand and tend to have an inflationary effect.

War means increased demand for many things, e.g., steel, armaments, the defence industry generally, and hospital and medical equipment. This means an instant increase in the level of aggregate demand.

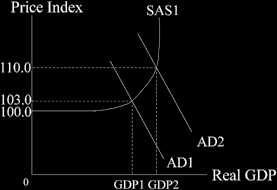

The effect of war on the macro economy: an increase in aggregate demand and inflation.

The invasion and occupation mean an increase in aggregate demand in the UK, a boost in output, with an associated increase in the level of employment, and extra inflationary pressures, as in the diagram above. (The figures are assumed and the movement exaggerated, in order to show the effects). The level of gross domestic product increases from GDP1 to GDP2, and inflation rises from 3.0 percent to 10.0 per cent.

• It also pushes up the price of oil because of the extra demand for oil to use in the war.

In the case of the Iraq war, there is the additional fear that the war may drift on for a long time and later could involve invasion into other countries in the Middle East. This means an increase in the price of petrol, as you or your parents will probably be well aware if you have a vehicle to run.

If the economy starts off in recession before the war:

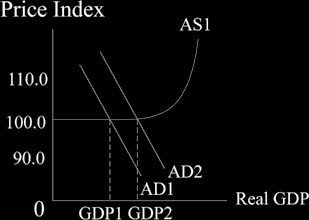

The war can be helpful as it brings the economy out of the recession. This happened in World War Two in 1939 when the British economy was stimulated, as was the American economy. There is a strong school of thought that says the efforts in the USA to boost their economy throughout the severe slump of the 1930s failed and only the advent of war stimulated a recovery. The diagram below shows an economy such as in the USA in the 1930s. An increase in demand would increase output and end the slump.

Starting a war in the middle of a recession

Demand increases, output expands, which means more jobs become available to those who are unemployed. Inflation does not increase as there is much spare capacity when we start.

But if the economy starts off at full employment:

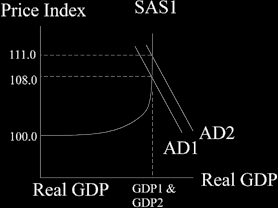

You will notice in the diagram below that no increase in output is possible, so the increased demand because of the war all spills over into a higher rate of inflation.

It is arguable that Britain had a strong and buoyant economy on the eve of the invasion of

Iraq, and so the full employment diagram below is perhaps the more relevant one. Starting a war when we already are close to full employment

The length of time involved

A short war can sometimes be helpful to an economy, especially when starting in a recession or slump. The initial increase in demand is real and boosts national income but being short the war is over quickly and the uncertainties vanish. On the other hand, the war diverts resources to engage in war that could be allocated to areas such as health, education, the private standard of living, pensions, or investment for future growth, so there is a real cost to society.

A long war is generally harmful. If it is conducted in part on home territory there will be much destruction of buildings and property. In these days of increased terrorism, there is likely to be some damage wherever the war is fought. The war can breed new uncertainties, divert investment towards the armaments industries away from consumer goods and services, which reduces the standard of living, as well as add to inflationary pressures.

A long time ago, a major recession was common after the end of a major war.

This seems to have happened over all human history, including the First World War (1914-18) Post-war there was a sudden fall in the level of aggregate demand. It was difficult to reallocate resources quickly to the sort of goods and services demanded in peace time and in addition the vast influx of discharged soldiers meant severe unemployment.

There is now less of a danger of this happening: because of the work of Keynes we know that government can increase the level of aggregate demand to offset the automatic fall that peace brings. This is how we avoided the emergence of a slump after the Second World War (1939-45) in the UK, the rest of Europe, and in the United States.

It is also now much quicker and easier to reallocate resources than it once was, which will help us after any major conflict in the future. This is the result of the changes begun by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher after 1979 in the labour markets and financial markets and perhaps to a lesser extent to the freedom given to the Bank of England to reduce interest rates to stimulate investment and consumption.

To list the ten goals with possible effects from the invasion of Iraq war:

• Economic growth: is boosted in the short term; but probably slowed in the longer term as resources go to waging war, rather than investing for the future.

• Allocation of resources: towards war goods and away from peace-time goods, such as education or health.

• Inflation: the war worsens the inflationary pressures; this is particularly noticeable in the price of petrol.

• Standard of living: reduces a bit; or at least not increases as much as it would otherwise have done.

• Distribution of income: moves towards the suppliers of armaments, munitions, uniforms and the like, as well as to the firms that reconstruct the Iraq economy when the war is over.

• Balance of payments: possibly harmed a little, as we probably had to import a few things with which to wage war; plus we probably lost a few exports as the goods or services were diverted to Iraq. The net effect is probably small?

• Value of the pound: probably not affected much.

As another example of an external shock and how to tackle it, let us look at the effects of a sustained rise in the price of crude oil.

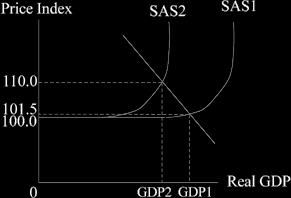

Unlike the previous example which was focused on the demand side, a sustained rise in the price of oil is a supply side problem. Such a price increase passes on through the general economy quickly because of the immediate increase in the price of transport and fuel. This increases the costs of virtually all producers and pushes up their micro supply curves. In turn, this means an immediate shift upwards in the aggregate supply curve.

Note: the figures are all assumed in order to demonstrate the principle involved.

The results can be read off the diagram: we see inflation increasing from 1.5 per cent to

10.0 per cent and the level of national income falling from GDP1 to GDP2. There is little

a government can do under the circumstances. It is unable to increase the level of aggregate demand to tackle the fall in output and the associated rise in unemployment, because we are already close to full capacity working and all we would see after a demand increase would be even more inflation. The only hope is to work on increasing the general level of efficiency in the economy and stimulating people’s motivation to work harder, i.e. to push the long run supply curve outward to the right. This by its nature is a slow process. For those governments of countries that are oil producers, such as the UK, it might make sense to promote the search for more oil beds, but this option is not open to most countries, as they totally lack oil.

Higher oil prices affect the supply of some things more than others, for example they have a disproportionate effect on the prices of petrol, bitumen and chemical fertilizer production all of which use crude oil as a major raw material. Such products suffer a substantial rise in price when the price of crude oil increases. The fear of a general world recession is likely to emerge and then grow.

So the rise in the price of crude oil helps those countries that are oil producers, and harms all oil importers. It can be particularly damaging to many third world countries as they rely on imports of chemical fertilizer for their agricultural production which is a large proportion of the economy. The agricultural output is used to feed the people and in

many cases to provide much-needed exports.

Notice that if you memorise and learn to manipulate the diagram for the determination of national income via aggregate demand and supply how useful it is. You can use it when tackling a great number of questions. And this is true not only in the exam room!

To list the ten goals with some possible effects from a substantial rise in the price of oil:

• Economic growth: this is harmed, as fuel and transport cost increase, forcing the short run aggregate supply curve upward.

• Allocation of resources: (not a lot to say here).

• Inflation: the oil price rise worsens any inflationary pressures.

• Standard of living: reduced a bit. To the extent that the tax on petrol is linked to the price of crude oil, the retail price of oil tends to rise immediately.

• Distribution of income: moved away from users of motor vehicles as they pay more for their petrol. The government also receives an increase in revenue from the automatic tax increase.

• Balance of payments: possibly helped a little, as the UK enjoys net exports of fuels.

• Value of the pound: probably not affected all that much? The adverse effect on growth might be offset by a positive effect from the balance of payments.