EXPLAINING THE DEHYDRATION OF ALCOHOLS

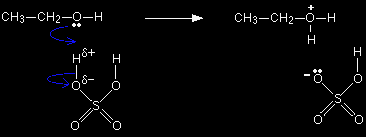

This page guides you through the mechanism for the acid catalysed dehydration of a simple alcohol like ethanol to give an alkene like ethene. Dehydration of more complicated alcohols is dealt with on a separate page. This is an essential part of this topic, and you should follow the link at the bottom of this page if you haven't already done so. The dehydration of ethanolThe full version of the mechanism This full version covers the mechanism using sulphuric acid. Afterwards, we'll look at the simplified version which will work for any acid, including phosphoric(V) acid. The oxygen atom in the ethanol has two active lone pairs of electrons, and one of these picks up a hydrogen ion from the sulphuric acid. The alcohol is said to be protonated.

|

|

|

Note: Only one of the lone pairs on the oxygen is being shown because only one is used in the reaction. Similarly, all the multitude of lone pairs in the sulphuric acid are omitted because they aren't relevant to the mechanism. If you aren't happy about the use of curly arrows in mechanisms, follow this link before you go on. Use the BACK button on your browser to return to this page. |

|

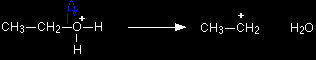

The negative ion produced is the hydrogensulphate ion, HSO4-. Notice that the oxygen atom in the alcohol has gained a positive charge. That charge has to be there for two reasons:

|

|

|

Note: Oxygen with a positive charge has the same arrangement of electrons as a nitrogen atom - which normally forms 3 bonds. |

|

|

In the second stage of the reaction the protonated ethanol loses a water molecule to leave a carbocation (previously known as a carbonium ion) - an ion with a positive charge on a carbon atom. The carbon atom is positive because it has lost the electron that it originally contributed to the carbon-oxygen bond. Both of the electrons in that bond have moved onto the oxygen atom, neutralising the oxygen's charge.

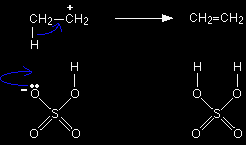

One of the several things that can now happen to this carbocation is for it to lose a hydrogen ion from the CH3 group. This hydrogen ion is pulled off by a hydrogensulphate ion to regenerate the sulphuric acid catalyst. |

|

|

Note: The other things that might happen to the carbocation lead to products like ethoxyethane and ethyl hydrogensulphate. The mechanisms for these aren't required by any current A' level syllabus. |

|

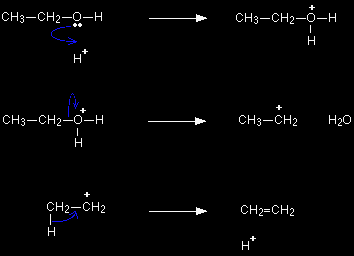

The simplified version of the mechanism Instead of showing the full structure of the sulphuric acid, it is commonly written as if it were simply a hydrogen ion, H+. An advantage of this (apart from the fact that it doesn't require you to draw the structure of sulphuric acid) is that it can be used for any acid catalyst without changing it at all. For example, if you use this version, you wouldn't need to worry about the structure of phosphoric(V) acid. AQA (the only Exam Board to demand the dehydration mechanism at the moment) is happy to accept this version.

In the first stage, the ethanol gets protonated exactly as before - the only difference is that you are writing H+ instead of the full structure of the sulphuric acid. The second stage is identical to the one in the full version of the mechanism. The final stage shows a hydrogen ion "falling off" the carbocation - rather than being pulled off. This is seriously misleading, but it's what the examiners want!

How to deal with more complicated cases . . . To menu of elimination reactions. . . |

|