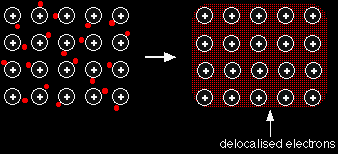

METALLIC BONDINGThis page introduces the bonding in metals. It explains how the metallic bond arises and why its strength varies from metal to metal. What is a metallic bond?Metallic bonding in sodium Metals tend to have high melting points and boiling points suggesting strong bonds between the atoms. Even a metal like sodium (melting point 97.8°C) melts at a considerably higher temperature than the element (neon) which precedes it in the Periodic Table. Sodium has the electronic structure 1s22s22p63s1. When sodium atoms come together, the electron in the 3s atomic orbital of one sodium atom shares space with the corresponding electron on a neighbouring atom to form a molecular orbital - in much the same sort of way that a covalent bond is formed. The difference, however, is that each sodium atom is being touched by eight other sodium atoms - and the sharing occurs between the central atom and the 3s orbitals on all of the eight other atoms. And each of these eight is in turn being touched by eight sodium atoms, which in turn are touched by eight atoms - and so on and so on, until you have taken in all the atoms in that lump of sodium. All of the 3s orbitals on all of the atoms overlap to give a vast number of molecular orbitals which extend over the whole piece of metal. There have to be huge numbers of molecular orbitals, of course, because any orbital can only hold two electrons. The electrons can move freely within these molecular orbitals, and so each electron becomes detached from its parent atom. The electrons are said to be delocalised. The metal is held together by the strong forces of attraction between the positive nuclei and the delocalised electrons.

This is sometimes described as "an array of positive ions in a sea of electrons". If you are going to use this view, beware! Is a metal made up of atoms or ions? It is made of atoms. Each positive centre in the diagram represents all the rest of the atom apart from the outer electron, but that electron hasn't been lost - it may no longer have an attachment to a particular atom, but it's still there in the structure. Sodium metal is therefore written as Na - not Na+. Metallic bonding in magnesium If you work through the same argument with magnesium, you end up with stronger bonds and so a higher melting point. Magnesium has the outer electronic structure 3s2. Both of these electrons become delocalised, so the "sea" has twice the electron density as it does in sodium. The remaining "ions" also have twice the charge (if you are going to use this particular view of the metal bond) and so there will be more attraction between "ions" and "sea". More realistically, each magnesium atom has one more proton in the nucleus than a sodium atom has, and so not only will there be a greater number of delocalised electrons, but there will also be a greater attraction for them. Magnesium atoms have a slightly smaller radius than sodium atoms, and so the delocalised electrons are closer to the nuclei. Each magnesium atom also has twelve near neighbours rather than sodium's eight. Both of these factors increase the strength of the bond still further. Metallic bonding in transition elements Transition metals tend to have particularly high melting points and boiling points. The reason is that they can involve the 3d electrons in the delocalisation as well as the 4s. The more electrons you can involve, the stronger the attractions tend to be. |

|

|

Note: If you aren't happy about the electronic structure of transition metals, then you might like to follow this link to revise it. |

|

The metallic bond in molten metals In a molten metal, the metallic bond is still present, although the ordered structure has been broken down. The metallic bond isn't fully broken until the metal boils. That means that boiling point is actually a better guide to the strength of the metallic bond than melting point is. On melting, the bond is loosened, not broken.

|

|